ARFID: more than picky eating

February 24, 2023

Everybody has met a picky eater in their life. Somebody who refuses a salad because of tomatoes, or somebody who mandates that their sandwich be prepared in a specific order. Most picky eating is harmless, but for some people, what looks like picky eating could be the manifestation of a mental health disorder.

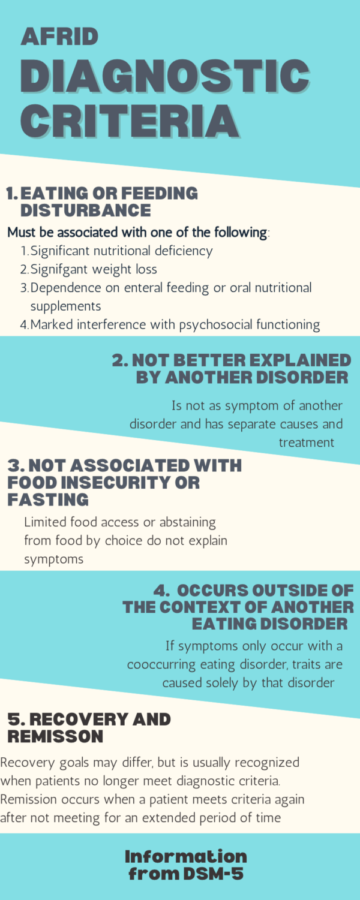

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder, or ARFID, is an eating disorder characterized by an inability to maintain a healthy weight or reach adequate nutrition due to a disinterest in food or concerns about the potential consequences of eating. These traits must interfere with one’s psychosocial functioning. AFRID is not about body size nor is it anorexia.

ARFID is a relatively new term that was introduced in 2013 upon the release of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Before that, many people who met the criteria for ARFID were unable to receive proper care and were diagnosed with “eating disorders not otherwise specified,” which did not correctly identify individuals’ symptoms.

ARFID is commonly associated with other psychiatric comorbidities including Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and anxiety. However, the preoccupation with food caused by these disorders varies widely.

There are three separate subtypes of ARFID, avoidant, aversive and restrictive.

People with avoidant ARFID avoid certain types of food due to sensory issues. They may be sensitive to scents, textures, or flavors overall.

Those with aversive ARFID experience fear-based reactions related to food. They may fear potentially choking or vomiting. Others with aversive ARFID may have OCD and rituals associated with eating, such as only eating foods in certain locations or at certain times.

Restrictive AFRID is the diagnosis given to those with extremely low appetites. These individuals often have little-to-no interest in food and forget to eat all together. They may also be selective about the foods that they will eat.

Sometimes individuals with ARFID develop more than one type of it. In cases like this, it is not unlikely for them to express features of other eating disorders. This combination of symptoms is termed AFRID plus.

There is no single causation for AFRID, though genetic factors, environmental influences, sociocultural factors, and other mental health conditions factor into the disorder’s development.

The health risks associated with AFRID include cardiac complications, heart problems, kidney and liver failure, bone density loss, anemia, electrolyte imbalance, low blood sugar, constipation, and gastrointestinal issues.

ARFID treatment varies patient by patient but must address the patient’s developmental history, internal and external goals, and family dynamics. One of the most common methods of treatment is therapy, such as Cognitive-behavioral therapy or Occupational therapy.

Medications can also be prescribed to treat AFRID. Common options include appetite stimulants, antihistamines, and anxiety medications.

Many people who seek treatment for AFRID require medical intervention, where a team of professionals work together on a case-by-case basis to determine the best actions to take for individual health.

Erica A. was diagnosed with avoidant ARFID when she was 19 years old. “ARFID makes it hard to eat enough daily & eat 3 meals a day,” she said. Along with AFRID, she has been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, anxiety, and PTSD.

Erica noted she would pick at her food and regularly throw a lot of it away. “It made me feel guilty to be wasting so much food, and I was scared others would think I was intentionally starving myself, which was not the case.”

This fear led to her avoiding eating around other people altogether. “I would just bring a bunch of junk food snacks to my room and that would be my food for the day.”

Eventually, her relationship with food began to affect her physically as well. Along with losing weight, Erica developed multiple severe vitamin deficiencies.

Thankfully, she has now entered recovery, which she describes as a “slow but rewarding process.”

Erica now takes Seroquel for her bipolar disorder and with proper dosage, her appetite is back. She has gained back the weight she lost and takes supplements for her vitamin deficiencies.

“My diet still isn’t the best, but it’s becoming less restrictive, and I am able to eat full meals again.”

Recovery is possible. If you or somebody you know is struggling with an eating disorder, do not hesitate to reach out for help from your doctor or hotlines