In-Depth: Native American Heritage Month throughout varying lenses

November 19, 2019

Violence Against Women Act extends to native women – Hailey Gillespie

Since George W. Bush released a presidential proclamation declaring November to be Native American Heritage month in 1990, the rights of Native peoples have seen many advancements.

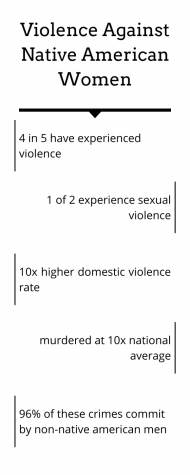

However, according to current statistics from the Indian Law Resource Center, 4 out of 5 Native American women will endure violence throughout their lifetimes, and 1 out of 2 will experience sexual violence.

Non-native men are said to commit 96% of these crimes.

VAWA, the Violence Against Women Act, was originally enacted into law in 1994, signed by Bill Clinton. On April 4th of this year, it was passed through the House of Congress with new provisions stated in the bill that directly impacted Native American women.

Before this, tribal councils did not have the right to pursue suspects of crimes committed on the reservations outside of the reservations. Nor however, did the federal government have the right to pursue anyone for crimes committed on native reservations.

This loophole meant that anyone could rape, abuse, and murder women on tribal lands, then leave and no one would have the jurisdiction to actively pursue them with legal repercussions.

VAWA’s goal is to address this crisis. Many Nebraska politicians were not so welcoming. According to the voting counts released, no Nebraska state Senators voted for the reauthorization of VAWA in 2019. Jeff Fortenberry voted present, Adrian Smith voted against, and Don Bacon voted against.

Don Bacon stated on Twitter that he did not vote for the bill because “it could have limited faith-based organizations,” continuing that it could have put their ability to receive grants in danger if they refused to contradict their religious beliefs.

He is primarily referring in this Twitter statement to language included in VAWA that did not limit its benefits to people with female reproductive organs at birth.

The implications of this would be that for an organization of any sort to receive grants from VAWA, they must accept all people identifying as female when providing shelter for battered victims.

Statements from other lawmakers in NE supporting VAWA were unable to be located for the 2019 reauthorization or the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women’s Act.

However, Republican Senator Deb Fischer did vote yes for the reauthorization of VAWA in 2013 before it included the revisions for Native American Women.

Wakefield details her Kiowa tribe heritage and frustrations – Hannah Miller

Sydney Wakefield, 9, has family heritage rooted with the Kiowa tribe of Oklahoma. Wakefield first started to research her Kiowa heritage in sixth grade because that is when she first joined the Native Indian Centered Education club (N.I.C.E).

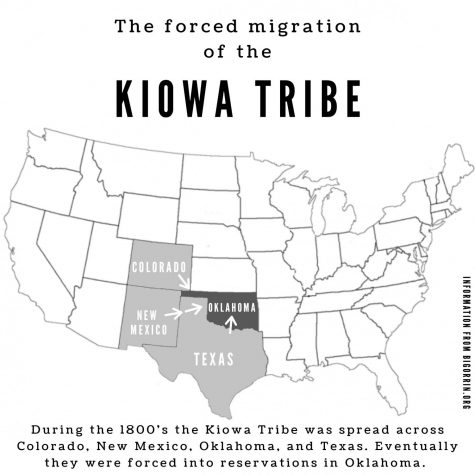

The tribe was originally spread across Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas until they were driven out of their lands with brutal force in the 1800’s. Many Native Americans that were forced to migrate into reservations were raped or murdered along the way, according to the Library of Congress.

“I like how my tribe was the one who didn’t take anybody’s crap like we weren’t friends with a lot of people but the people we were friends with we had connections with we were tight,” said Wakefield.

Wakefield does not know of any relatives who live on the Kiowa reservation, but she knows her grandpa, Andrew Wakefield, has some relatives there.

As a small child he was taken away from his biological family by CPS due to racist rationales and given to,” white parents,”. Mr. Wakefield’s two sisters were adopted around the same time he was. As the years of childhood has passed, he has finally been able to meet his biological family which includes three other half-brothers.

Adam Mazo of Somerville’s Upstander Project has helped to co-produce a documentary detailing the forced removal of Native American children from their parents, specifically in the state of Maine.

Mazo details the problem of Native American children being stolen from their families not unique to Maine and that it has been taking, “place for decades and centuries.”

Wakefield feels like the government tends to not care for Native Americans, “because they feel like it’s not really their problem. I think it’s like, ‘This is what my ancestors did it no longer applies to us the reservations are good, they have money, they have food, and they have everything they need,’ but poverty rates are up and suicide rates are up.”

According to the United States Census Bureau 26.2% of single-race American Indian and Alaska Native people were in poverty in 2016, the highest rate of any race group. For the nation, the poverty rate was 14.0 percent.

Suicide in the Native American and Alaskan Native community increased significantly between 1999 to 2017 compared to all other ethnic groups except for non-Hispanic Asians or Pacific Islanders, according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

The largest increase occurred for non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) females by 139%, from 4.6% to 11.0%. As for non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native males the percentage increased by 71%, from 19.8% to 33.8%, stated the CDC.

Effort is a practice Wakefield wishes the government would carry out in terms of understanding where Native Americans are coming from.

“I imagine if I lived [on a reservation] I would be kind of pissed off at the government. They forced [Native Americans] into a small land and they have little to nothing, but I just want to see them bring more awareness to it,” said Wakefield.

With lack of awareness, Wakefield experienced a racist remark while she was in the eighth grade.

Wakefield bet her teacher couldn’t find out her middle name. When her teacher searched it up on Canvas, he not only found out her middle name but also that she’s Native American.

To join the conversation Wakefield’s said her classmate said she was from, “Italy or Germany or something,” Wakefield jokingly responded with, “Oh all those white people countries.”

Wakefield was trying to joke around. Her teacher laughed. Then her classmate turned to look at her and said,

“Well at least my people didn’t live like freaking animals.”

The eighth-grade teacher, “did nothing about it, is the bad thing he’s like ‘Listen you can’t say that,’ and then just left it at that.”

After that moment Wakefield didn’t know what to do except to remove herself from the room.

“I couldn’t do anything but laugh at the time because I was so mad that somebody would say that,” said Wakefield.

Irony comes across Wakefield’s mind when her entire family celebrates Thanksgiving. Her grandfather grew up with “white people,” so he carried on the tradition with his family.

Wakefield questions the practice thinking, “Why are we celebrating this when the reason it started was because something terrible happened?”

For Wakefield in her elementary school, they played, “Pilgrims and Indians” per Thanksgiving holiday tradition. She and like millions of other children were also taught that, “Oh we [Pilgrims and Native Americans] were all friends and Thanksgiving was a happy time.”

Genocide, racism and rape are among the few major factors that affected many Native American tribes when North and South America was being colonized and Wakefield understands that they wouldn’t teach all of that to five- and six-year-olds.

But for Wakefield, “it just kind of sucks to grow up and just like to learn that everything you’ve grown up knowing we were all tight and stuff is a lie.”

Wakefield realizing the lies the school system taught her makes her wish there was more representation of Native Americans in the media.

“I’ve never seen like a full on Native American tv show,” said Wakefield.

If there were to be a show with a fully Native American cast, Wakefield hopes that it would show what life is like growing up on a Reservation, “and then the tale of these people and how they actually went out into the world, after the Rez, made enough money and brought it home to their families.”

Students prepare for a N.I.C.E. future – Jeremiah Booth

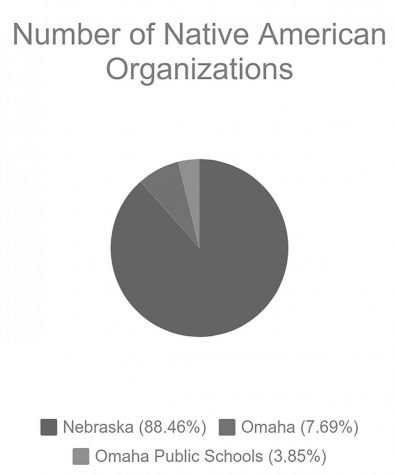

N.I.C.E is an acronym that stands for Native Indigenous Centered Education. N.I.C.E engages Native American students in a way that speaks to them so that they can be successful in school. They do this by supporting Native American culture, language, educational sovereignty, and addressing the kids’ other needs such as college preparation or preparation for their future careers.

“I personally hope to help facilitate them to build a strong self-identity so they can successfully navigate an urban mainstream high school experience. It’s important that we do that because many Native students come from different backgrounds and often us as Native people and our Native history is forgotten,” said Tara Burnette, OPS N.I.C.E Director.

They are currently looking into inviting “The Circle of Grandmothers” to come and speak at Omaha North sometime in November. It’s currently pending approval from administration, according to Tara Burnette. If the Circle of Grandmothers come, they will answer questions formulated by N.I.C.E students and any other students who have questions. “I foresee questions pertaining to Indianness, identity, stereotypes, and what an urban native is,” said Tara Burnette.

The Circle of Grandmothers is a group of elder Native American grandmothers in the Omaha area and represent many tribes, such as the Ponca Tribe and the Omaha Tribe. They work closely with Minnesota Humanities, which is a statewide nonprofit and full-service event center located in St. Paul, Minnesota. The Circle of Grandmothers presents a lot to OPS teachers about life experiences and how history plays into their lives as Native Americans and have been doing this for about 7 years according to Tara Burnette.

N.I.C.E is visiting The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Tuesday, Nov. 12th. They are visiting for a Symposium that will expose the students to UNL’s campus and connect them with potential resources for the cost of attendance. The theme will be #WeAretheChange and the students will be doing a variety of things such as discovering the many ways Nebraska can provide the tools they need to establish a strong foundation for success, from learning how to apply to college to engaging with community members on trending issues.

All N.I.C.E members are welcome to attend the trip. There will also be a community engagement panel that “will engage community members to explore topics from your perspective and through the lens of others in the community,” UNL Admissions.