Art series targets gender-based street harassment through portraits of survivors

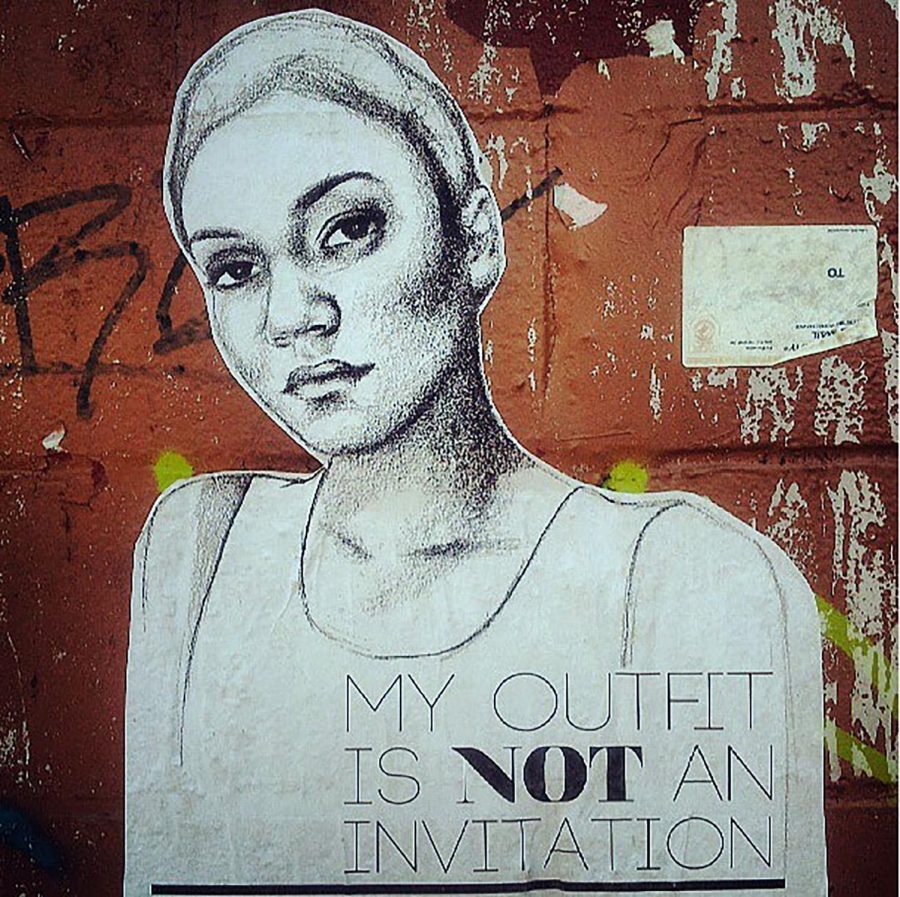

This is one example of Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s portraits that she wheat pastes around the world to send a message to street-harassers. Photo courtesy of Stop Telling Women to Smile (STWTS)

February 12, 2019

In the fall of 2012 in Brooklyn, NY, a street art series focusing on genderbased street harassment was born. It is known as Stop Telling Women To Smile (STWTS), and its creator is named Tatyana Fazlalizadeh. She is an illustrator and painter and is based in Brooklyn but has branched out into street art as a muralist.

Stop Street Harassment’s definition for gender-based street harassment is, “unwanted comments, gestures, and actions forced on a stranger in a public place without their consent and is directed at them because of their actual or perceived sex, gender, gender expression, or sexual orientation.”

More examples of street harassment include, unwanted whistling, leering, sexist, homophobic or transphobic slurs, persistent requests for someone’s name, number or destination after they’ve said no. This also includes, sexual names, comments and demands, following, flashing, public masturbation, groping, sexual assault, and rape.

Since the birth of STWTS, it has been an on-going travelling art series and has been in many cities, but is not limited to, Paris, France, Mexico City, Mexico, and Chicago, Illinois.

“I started it because I wanted to talk about my experiences with street harassment. It was my way of speaking back to my harassers, guys who say things to me on the street who are unwelcome, unwanted, or aggressive, and really make you feel uncomfortable and harassed,” said Fazlalizadeh in a video on her website Stop Telling Women To Smile.

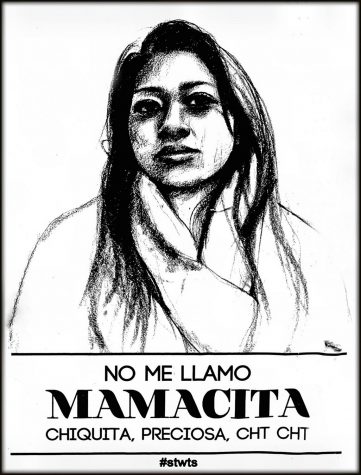

Fazlalizadeh sits down with her subjects and talks about street harassment and their personal experiences involving it. She listens to their stories and what they want their harassers to hear. Then she comes up with a caption for the poster that is inspired by what they told her.

“I’m putting a face to these words. Not just a ‘Hey street harassment is bad,’ you actually get to see this persons’ face, this woman’s face who goes through this daily and what she wants to say about it,” said Fazalalizadeh.

She designs the posters, prints them out, and goes out and wheat pastes them onto walls. Wheat paste is a gel or liquid adhesive made from wheat flour or starch and water.

Photo courtesy of STWTS

“Wheat pasting it’s really fun. I feel like it’s a great and perfect medium for this project. I make the wheat paste at home usually,” Fazlalizadeh said.

Fazlalizadeh tries to put them up in the area where the woman lives, or where she feels close to the street harassment.

“I realize that street harassment doesn’t happen in one community. It doesn’t happen in one neighborhood. It happens everywhere, and so I try to spread these posters out and cover a lot of ground,” Fazlalizadeh said.

For people who want to wheat paste Fazlalizadeh’s STWTS posters they are available to download on her website, Stop Telling Women To Smile.

There are six free posters to choose from and a few of them read, “My outfit is not an invitation,” “Women are not outside for your entertainment,” and “You are not entitled to my body.”

Stop Street Harassment put out a 2,000-person nationally representative survey in the USA with the firm GfK.

According to Stop Street Harassment, “The survey found that 65% of all women had experienced street harassment. Among all women, 23% had been sexually touched, 20% had been followed, and 9% had been forced to do something sexual. Among men, 25% had been street harassed (a higher percentage of LGBT-identified men than heterosexual men reported this) and their most common form of harassment was homophobic or transphobic slurs (9%).”

Ingrid Howell, Central High alumnus and co-owner of Well Grounded, coffee shop on 14th and Leavenworth, has experienced a ton of street harassment.

“It doesn’t matter what I’m wearing, if I’m completely covered in sweats, but a man can still tell that I’m a woman, I get catcalled or worse. So, I’ve stopped dressing to cover up for that because it doesn’t make a difference either way,” Howell said.

To Howell, being cat called makes her feel awful, unsafe, disgusting, and it makes her angry in every part of her body. Howell feels like she has to scream, “This is my body, MY BODY! Not yours to comment on, not yours to threaten,” every time it occurs.

“It feels like a violation before there’s even physical contact and then if there is any, it feels like the world is over for me that day, maybe week, who knows, it’s super gross,” said Howell.

Howell said that the catcalling gets more aggressive when she makes less eye contact with the harasser.

“[I get called a] ‘b—-’ frequently and get the whole line ‘f— you b—-’ said louder as I hurry away,” Howell said.

According to an organization called Holla Back, a few ways to respond to harassers include, “Look them in the eye and denounce their behavior with a strong, clear voice. Don’t engage.”

Holla Back also stated that harassers may try to argue with their target or make fun of them. Once you’ve said your piece, ”keep it moving. Harassers don’t deserve the pleasure of your company. Share your story.”